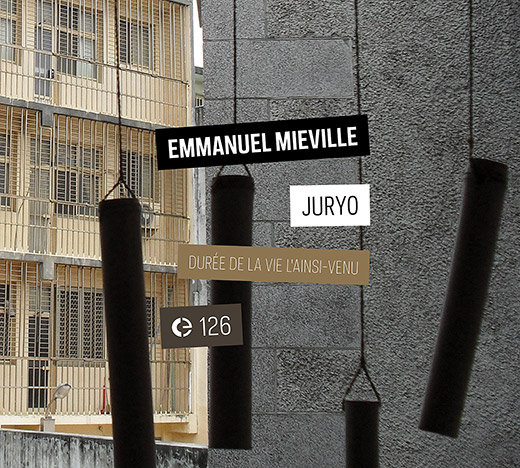

The title of the latest album by the super-prolific experimental composer and student of film and musique concrete, Emmanuel Mieville, comes from the Japanese translation of the Sanskrit word and alludes to a chapter of the Lotus Sutra, a renowned text from MÄhÄyana Buddhism. Apparently. It’s hardly my field of expertise. And so the inevitable question arises: what’s my point of entry?

Juryo is by no means an accessible album and its four longform tracks, which span between nine and eighteen minutes don’t readily lend themselves to lengthy debates about Buddhism and the path to enlightenment. Similarly, that the album consists of four compositions shows no obvious correlation with the twenty-eight chapters of the Lotus Sutra. As such, it’s fair to surmise that the allusion which connects the title to the contents is in largely an oblique one, beyond the fact that the album features field recordings captured in Asia.

This is swampy, abstract, murky noise. On the surface, it’s a formless conglomeration of noise, grating, grinding scrapes and bumps. Woozy rippling bubbles flit and floom over tidal waves of surging extranea, which may or may not be the swash of actual water rippling over rocks: it could equally be an aural illusion, or an intentional simulacrum.

Top-end whistles sustain for an eternity and aggravate not only the aural receptors but the mind on ‘Nyorai’, although in the mix are recordings of Tibetan nuns and FM radio from Hong Kong. These manifests as chants and clattering chimes and finger cymbals which emerge around the midpoint of the seventeen-minute sonic journey. According to the liner notes, ‘Murasaki’ means ‘purple’ in Japanese, but the spinning, swirling sonic discombobulations which eddy and swirl present a kaleidoscopic vista.

In the sleeve notes, Mieville explains that ‘Taisi Funeral’ (the fourth and final track) is a ‘recording of Buddhist chanting for a deceased person recorded in a small village in Taiwan, mingled with my own synthetic sounds. Tanit Astarté is a quotation from Antonin Artaud’s book Héliogabale and refers to the moon goddess, as described in Phoenician myths’. It’s certainly the most overtly musical and rhythmic of the four compositions, but as a rising surge of amorphous sound rises to wash away the voices and the rhythm peters out, it transforms to an altogether more ambient soundscape. Morever, while still linking back to the overarching theme of the Lotus Sutra, we can see that Meiville’s sphere of reference is considerably broader than may first appear.

Juryo is subtly complex and had both range and depth. It doesn’t readily conform to any one genre, but to lazily slot it into the broad space occupied by ‘experimental / avant-garde’ is to fail to recognise the spectrum of stylistic elements it incorporates. Christopher Nosnibor