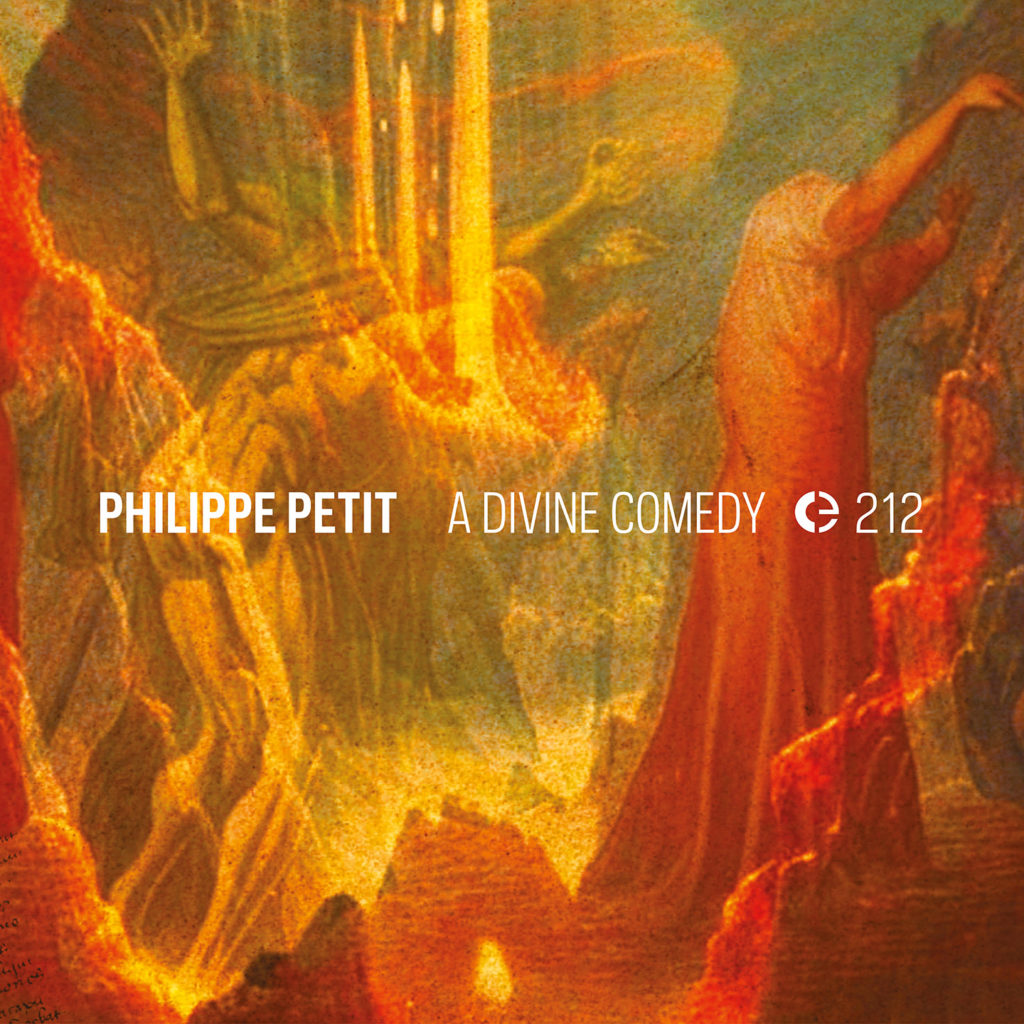

Ah, “A Divine Comedy”! A title as grandiose as the task at hand, and yet Philippe Petit, the ever-ambitious sonic alchemist, dives headlong into the inferno with a flair for the dramatic that would make even Dante blush. This double album is not merely a nod to Alighieri’s epic poem; it’s a full-on, spiraling descent into a hellscape of sound where the rules of classical narrative are gleefully cast aside in favor of something far more abstract—and far more unsettling.

The first disc, aptly titled “Inferno”, opens with “Halas Jacta Est”, a track that sets the stage for the chaos to come. Petit’s use of modular synthesis and acousmatic spatialization creates an atmosphere thick with tension, as though you’ve just stumbled into the ninth circle of Hell and are beginning to question all your life choices. There’s a sense of foreboding, a sonic warning that what follows will not be a leisurely stroll through the underworld, but rather a plunge into its most nightmarish depths.

Tracks like “Within the Corridors of Hell…” and “Lucifer, Fallen Angel” do not disappoint. The former is a claustrophobic journey through echoing, dissonant corridors where each sound feels like a spectral whisper in your ear, while the latter plays out like a symphony conducted by the devil himself—chaotic, malevolent, and disturbingly beautiful. Petit’s manipulation of sound is masterful here; it’s as though he’s using his modular synths to paint a picture in shades of black, each note a brushstroke in the murky abyss.

Yet, as with Dante’s journey, there is a light at the end of the tunnel—if you can survive long enough to reach it. The second disc, beginning with “Purgatorio, Canto I”, offers a semblance of relief. The music here is less oppressive, though no less complex. Petit shifts his palette, introducing lighter tones that suggest a tentative ascent toward redemption. The mood is reflective, almost meditative, but always with that underlying sense of unease, as if reminding us that Purgatory is not a vacation—it’s a state of transition, fraught with its own trials and tribulations.

“Paradiso, Canto I” and “Paradiso, Canto II” close out the album on a somewhat hopeful note, but don’t expect a Hollywood ending. Petit’s interpretation of Paradise is less about celestial choirs and more about the fragile, fleeting beauty of transcendence. The final notes of “Paradiso, Canto II” hang in the air like a question mark, unresolved, leaving the listener to ponder the journey they’ve just experienced.

For those familiar with Petit’s vast body of work, “A Divine Comedy” is both a continuation and a departure. His love for modular synthesis and electroacoustic manipulation is on full display, yet there’s a conceptual weight here that sets this album apart. It’s clear that Petit isn’t just playing with sound — he’s wrestling with the very fabric of narrative and emotion, distorting them until they barely resemble their original forms. It’s Expressionism in its purest sense, where reality is twisted to provoke a visceral response.

But be warned: this is not an album for the faint of heart. Petit’s “A Divine Comedy” demands patience, attention, and perhaps a touch of masochism. It’s a dense, challenging work that offers no easy answers, no comforting melodies to hum along to. Yet, for those willing to descend into its depths, the rewards are immense. It’s a journey that mirrors Dante’s own—harrowing, transformative, and ultimately, unforgettable.

So, if you’re ready to trade your earthly comforts for a trip through the sonic underworld, “A Divine Comedy” awaits. Just remember, as you press play: “Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate”. Abandon all hope, ye who enter here. And enjoy the ride. Vito Camarretta

via Chain DLK