Attributing a value to forlorn locations through the assessment of their resonant qualities represents a sort of transference of power. When a sound artist – presumably gifted with deeply perceptive features – sets conditions for a given structure to vibrate, the spontaneous generation of a different type of life occurs. The resulting interaction gains or loses strength according to contingent forces at work, but – sure enough – the hugeness of a reverberation is one of the few things able to connect the most audacious experiment to the realization of being, after all, extremely limited.

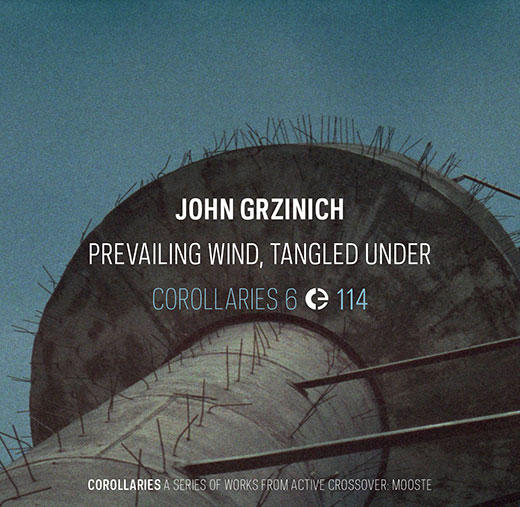

John Grzinich – assisted in some of these recordings by Simon Whetham and Arlene Tucker – is one of the best “men for the job†when it comes to producing sonic elements with a purpose from materials that would appear as good as dead to the average observer. In Prevailing Wind, Tangled Under he sensibly elected to let a water tower in Mooste, Estonia express its acoustic vigor without interruptions. A modicum of variety in the timbral gamut comes from what the mastermind describes as “crawling about, climbing, plucking, bowing, striking, howling, stringing and generally playingâ€. The 46 minutes reveal a practical harmonization between the human and the (theoretically) inanimate. Occasionally, a welcome complement – the chanting of assorted species of birds – introduces further suggestions beyond the ominous roars, wavering frequencies and various clangors characterizing at large the textural mass.

The whole transmits a sense of conscious persistence, in a way symbolizing an obstinate attempt to distil juices of critical energy in places where most people’s logic would suggest a refusal of possibilities. Molecules are everywhere, though; hence, our weight in the universal ambit equals that of a rock (or a water tower, for that matter). Better learn the lesson once and for all. Massimo Ricci